The novel I have been writing for the last few months involves a wealthy American family from New York and an English nobleman. While building the story line and characters, I realized I needed more information about the hundreds of Old Master paintings that had once graced the dining rooms, entry halls and sitting rooms of castles, Mayfair mansions and country estates across England. How exactly did they end up across The Pond (aka the Atlantic Ocean), ultimately gracing the walls of American mansions and art museums around the turn of the century?

I knew that England’s aristocracy was on the decline by the First World War as the result of changing political sentiment and representation among the working class, the loss of power in the House of Lords, estate taxes and the overall loss of income from the agricultural depression of the 1870s. I didn’t realize as I embarked on my quest that I would find myself running down a rabbit hole to learn more than what I had originally set out to discover.

Ask any writer, and she or he will probably tell you that the research bit is the most difficult part of creating a great piece of historical fiction. And most will say just as emphatically that it is an equally exciting part of the craft. For myself as a self-proclaimed history nerd, I love creating my own little worlds through storytelling and the research feeds my ever-inquisitive brain along the way. I often find myself distracted by questions that arise as I create settings or develop characters and then off on an adventure I go! It was no different this time. My treasure hunt for Old Masters in America at the turn of the century led me to a big X marks the spot: I found a book on the subject AND it was actually available through my local library! Eureka!

The book I discovered was Old Masters, New World: America’s Raid on Europe’s Great Pictures, by Cynthia Saltzman and it was an incredible find! Saltzman used primary sources of information gleaned through researching museum archives, family letters and historical periodicals to create this extraordinary piece of art history: exactly the kind of real information I needed to fill in my knowledge gaps. I learned who the players were on the English side, who was capitalizing on brokering deals with fresh American money and who ultimately benefited from the sales of these centuries-old masterpieces.

Saltzman begins with Henry Marquand and his early acquisitions for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City from an old estate in England. She continues to Bernard Berenson and his work with Otto Gutekunst of the P & D Colnaghi & Co gallery in London, brokering for Gardner to build her massive art collection (which would become the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston) and ultimately ends at Frick’s mood swings and his million dollar obsession with art.

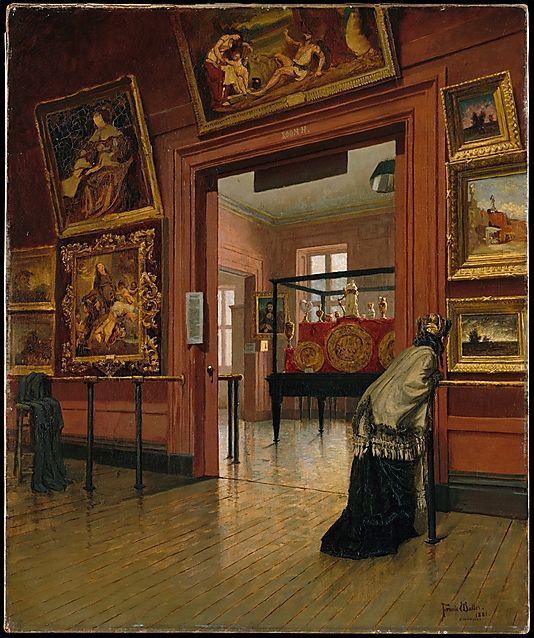

It fascinated me to learn about the Titians, Rembrandts, El Grecos and Vermeers that made the transatlantic voyage, among so many other important works of art. Through her fantastic descriptions, Saltzman includes the stories of the artists, the subjects of the masterpieces, and where the pictures ultimately came to rest in the United States. She outlines the deals and haggling which occurred over telegrams and phone calls between the noblemen, the galleries, the brokers and the Americans. The only downfall I found while reading was that I had to search for images of some of the artwork discussed: there are about 15 color images in the middle of the book, but there are at least twice as many paintings discussed throughout – thank goodness for Google!

The rabbit hole of Cynthia Saltzman’s book has now led me to David Cannadine’s The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy. In it, Cannadine covers the social, political and economical facets of the time period. While this tome is a bit drier, I am excited to learn even more about this piece of British history which aligns with the Guilded Age in America. Who knows how far down this rabbit hole I’ll keep going…