The first John Jacob Astor arrived in America from Walldorf, Germany in the late 1700’s after the Revolutionary War. Over the course of his lifetime he held many professions: butcher, like his father; instrument maker and dealer, like both his brother and uncle; furrier; tradesman; and real estate investor. By 1810, when he was in his late forties, he had been married for twenty-five years and had eight children, five of whom lived to adulthood. In the relatively short time he had been in the US, John Jacob had also risen to become a well-rounded, wealthy, self-made American business man.

John Jacob’s political connections, sheer ingenuity and hard work fueled the creation of his initial fortune. He was known to be ruthless, aggressive and self-serving in his quest to make money and by this time, he had mastered the ever-changing trade cycle with China (including the darker side which involved opium smuggling) and reaped incredible profits from the venture. Within another ten years, he would overtake the British monopoly on the fur trade, and control the majority of the fur market throughout most of North America.

John Jacob’s ultimate goal for America’s fur trade was to create a transcontinental network of fur outposts scattered from the northeast of the continent to the unsettled western boundary. Time was not on his side when he attempted to establish the first Pacific Northwest settlement, which he called Astoria, amidst the Oregon territory. He sent two groups to settle the area: one sailed from New York down the Atlantic, around the Horn of South America and back up the Pacific Ocean, to arrive at the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon; the second group followed the path laid out by Lewis and Clarke across North America. As they traveled, they were supposed to establish additional outposts along the way. The Astoria outpost was meant to become a clearing house of the furs collected from the other posts, which would then be shipped directly to China for trade.

Unfortunately, when he made his move to conquer the fur trade across the continent, the men he had chosen to lead the venture were not the leaders he thought them to be. They were incredibly disorganized, unethical and did not act in John Jacob’s best interests. In addition to his poor choice in expedition leadership, the United States and its old foe, England, had once again found themselves at war. Trade was interrupted, and the US government was occupied with fighting embargoes and attempting to find a diplomatic end to the issues plaguing it; its priority was not expanding the new nation’s territory. John Jacob was left with nothing to show and the entire venture was a costly disaster (some estimates say to the tune of $1 million). In the end, England claimed the outpost and renamed it Fort George, and it would remain as such until the US reclaimed the territory many years later.

By the late 1820’s, through rumored payouts to politicians and the exploitation of Native Americans, John Jacob would finally gain control of the fur trade and hold the monopoly under his American Fur Company. It was also around this time that he had begun to let William Backhouse Astor, his second son (whom he had named after his early mentor in the fur trade) take the wheel of his various enterprises under the Astor & Son company.

Once William was established at his office in New York, John Jacob took time away from his trading enterprise to travel to Europe with his youngest daughter Eliza. The initial reason for the departure was to end her romance with a young New York dentist whom she was hoping to marry. John Jacob found the young man unsuitable, especially in light of his eldest daughter, Magdalen’s two failed marriages and the elopement of his middle daughter Dorothea (whom he would disinherit only to reconnect with several years later). Eliza was married off to Count Vincent von Rumpff, a minister for Paris. She would die twelve years later, some said of a broken heart, at the age of thirty-seven.

While William maintained the day to day business operations in New York, John Jacob reconnected with his German relations in Europe and introduced them to his growing family. He dined with European diplomats and was introduced to Louis-Phillipe, the Citizen King of France. Throughout all of his travels across America, Europe and Asia, John Jacob was not known to be cultured or polished, and his English was halting and heavily accented. However, he was said to be a charming, solicitous and pleasant guest full of stories he willingly shared with any who wished to listen.

Nearing his seventies, John Jacob began to dismantle the fur and trade companies; those industries had served him well, but he no longer had the mental stamina to continue to forecast the markets for potential profits. In 1834 his wife Sarah died, and within a few years so had his oldest daughter Magdalen, his sister Catherine, and his brother Henry. He faced a crossroads at this late juncture of his life and turned his focus from trade to acquiring more Manhattan real estate.

His portfolio had always included land: in years past, he was known to purchase lots, subdivide them and then lease the land to others for improvements. When the leases expired, he could renegotiate the contract or hold the mortgage should the lessor wish to buy. By handling his properties in this manner, he avoided paying taxes on the properties out of his own pocket and if the mortgagee reneged on the loan, he quickly foreclosed and took possession of the property to resell it. This practice only cemented the view his tenants and fellow businessmen shared of him: he was exacting, aggressive and unforgiving.

The new focus in long term real estate investment was intended to create even more wealth for his progeny. He demolished the building on Broadway, which he had called home with Sarah for decades, and built the Park Hotel, later changing its name to the Astor House. The hotel boasted multiple shops, and catered to the very wealthy. It was the most luxurious hotel of its time and well known by royalty and others of upper-class status. He built a new brownstone mansion for himself farther up Broadway where he spent the last decade or so of his life trying to improve his reputation. He enlisted his friend, Washington Irving, to document the adventure of the Astoria outpost as a way to begin to circumvent this view. The release of the book Astoria in 1836 did little to change people’s perspectives about him, but it did bring a colorful narrative to the forefront, detailing the industry, economy and politics of that time.

John Jacob spent his last few years living in the brownstone on Broadway, which he filled with the art and furniture he’d acquired throughout his travels across North America, Europe and Asia. He surrounded himself with up and coming poets, musicians and other artists, as well as the sea captains and merchants he’d befriended and worked with over the years. He never fully repaired his reputation, although those that really knew him, respected and spoke well of him.

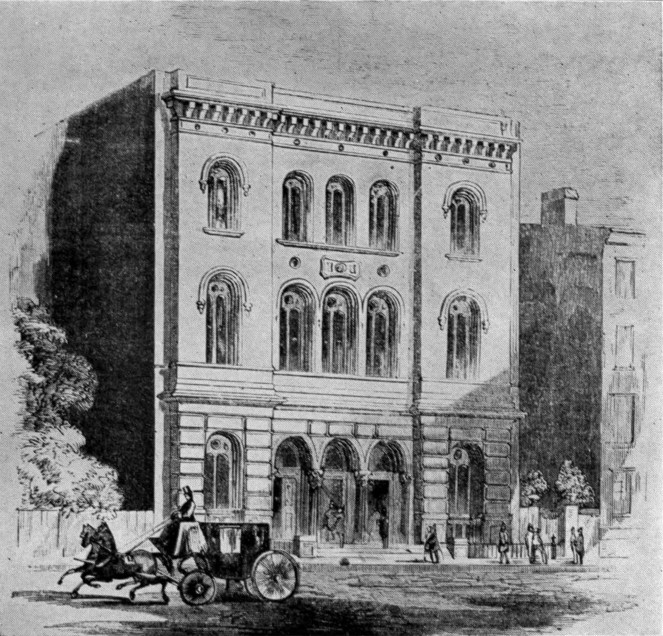

In the end, John Jacob Astor’s most lasting benevolent legacy was the $400,000 he set aside to build the Astor Library at the corner of Arts Street and Lafayette Place, which would be completed in 1854, and almost six years after his death. The Astor Library would later consolidate with other trusts to become the New York Public Library. Its Astor collection contains most of the rare editions the library is known for today.

Astor Library, NYC

Astor Library, NYCAt the time of his death, in 1848 at the age of 84, John Jacob Astor owned an estimated $2.5 million worth of land, which bordered 5th Avenue, 42nd Street, the Hudson River and Central Park. The majority of his estate would be left to William, with smaller portions set up in trust for his remaining children and grandchildren. The long term profit he sought to pass down would become both a blessing and a curse to those who were in line to inherit it.

Sources: The Astors, Derek Wilson, 1993 and Dynasty: The Astors and Their Times, David Sinclair, 1984

This is wonderful!

LikeLike