The third generation in the line of the strict male primogeniture created by John Jacob Astor I’s will was the first generation to live entirely under the wealth and inheritance amassed by the first two generations. Long gone were the days of that first Astor in America: there was no longer a need for fur trading posts across the continental US, nor was there a need to sail to the East to stock up on silks and spices. What began as a very small venture built upon the mercantile industry in the late 1700s had grown into a real estate empire under the prudent and often ruthless tactics of the heir of the second generation, William Backhouse Astor Sr. Upon his death in 1875, his sons inherited over $50 million each: one would retain control of a real estate business he didn’t really want, and the other would be overshadowed by his wife and live a life full of leisure and resentment.

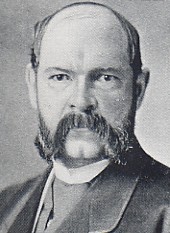

John Jacob Astor III, the first born son and heir of the Astor business empire, was born in 1822. He was a world apart in demeanor from both his father and his grandfather. His motto was “work hard, but only before dinner” and he exemplified the personage of a gentleman in the new American Aristocracy: he played at working hard to spend his family’s vast wealth.

In 1847, at the age of twenty-five, John married Charlotte Augusta Gibbes, and while John most certainly brought wealth to their match, Augusta (as she was called by friends and family) was from a southern family and brought the noblesse oblige, class and grace. By this time in his young life, John had already “failed of distinction” at Columbia, had attended Gottingen University like his father and grandfather, and also spent a year at Harvard Law School, but a scholar he was not. After he completed his time at the universities and before his wedding, he spent two years in Europe on his Grand Tour; the journey affirmed his love of the Old World aristocratic ideal that being a gentleman was far more important than being a businessman. John had minimal ambition and was content to spend as little time as possible in the family’s Prince Street offices. Once married, he and Charlotte would go on to have only have one child, William Waldorf, who in his adult life would snub New York Society for a British title and take on the life of a true European aristocrat.

Born in 1830, William Backhouse Jr, was the polar opposite of his brother. Outgoing, boisterous and academic, he excelled in school and graduated second in his class at Columbia. As the second son and younger brother of the Astor heir, he was forced to the shadows. He knew he would never inherit the Astor empire and did not seek anything beyond the place that was created for him: William resented the favoritism his father bestowed on John as the heir. The two brothers did not get along and it was a rivalry that would carry into the next generation.

William married Caroline Webster Schermerhorn (or Lina, as she was known to those close to her) in 1853. She was everything he was not: plain to his handsome and dumpy to his dazzling charm. Above all, she was very desperate to climb the New York social strata and claim her place at the very top; William’s vast wealth was the weapon she chose to arm herself with for the battle.

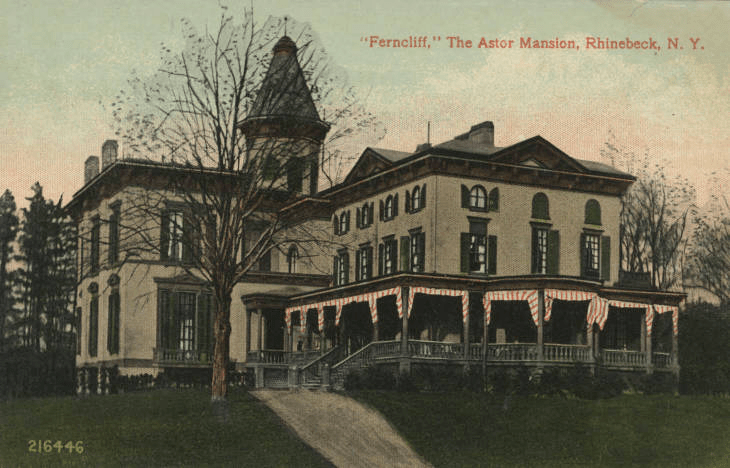

William and Caroline were childhood neighbors from LaFayette Place and had absolutely nothing in common. She did not enjoy literature, the arts, horses or sailing; she took no pleasure in any of the pursuits William held dear. Theirs was a poor marriage that produced four girls in the first nine years and finally, the only boy in 1864. After John Jacob IV’s birth, William was largely off on his own, drinking and carousing, traveling via his yachts or tending his farm and horse breeding facility at Ferncliff, his Hudson River estate in Rhinebeck, New York. He and Caroline only spent a few weeks a year together, which suited their disastrous relationship quite well.

John, who was most certainly not cut out to fully engage in the day to day of the family business, found his calling as the Civil War loomed. He donated funds to the Union cause and joined the effort as a Colonel under General McClellan. Charlotte abandoned her southern roots to the Union cause as well: she raised the 20th Infantry of Negroes, based in New York, and sent them off with a speech worthy of a great orator. John’s role as aide-de-camp under McClelland only lasted a short-lived eight months due to poor strategy and performance on McClelland’s part at Richmond and again later at Antietam. Astor resigned his commission, but continued to monetarily support the cause, earning himself a rank of Brigadier General. It was a rank he never used, preferring the rank of Colonel he’d had when attending the regimentals. William Backhouse Sr, opposed his oldest son’s involvement in the War and expressly forbade William Backhouse Jr from enlisting, even though the younger had already raised a regiment.

John Jacob III was the first Astor, probably because of Charlotte’s influence, to have something which resembled a social conscience. His multiple travels throughout Europe over the years of their marriage shaped his view of the responsibilities he held as the head of an old money family, and saw it as his duty to assist via public service. John and Charlotte were staunchly Episcopalian and served on various charitable boards. Charlotte spent the Astor money philanthropically through donations to the Children’s Aid Society and over $250,000 to the building of a memorial hospital for cancer treatment.

At the same time that John and Charlotte were spending Astor money benevolently, William Sr, still at the helm of the Astor business dealings, raised the rents of the slum tenements by ten percent. John did not recognize the opportunity to make a real difference for those less fortunate living in the family’s holdings and for the next twenty years, the Astor real estate dynasty fought tenement improvement initiatives all in the name of maintaining the five million dollars per year the rents gave them. The southern tier of the City was severely overcrowded; the Astors unscrupulously retained their hold on their northern acreage and even opposed the subway and elevated train plans which were developed to improve cross-city transportation for those who would choose to live farther from work. Their machinations attempted to prevent the loss of property value among their beloved Broadway holdings and fueled their reputation of valuing money over humanity, ultimately carrying on the legacy of greed that had been cultivated for almost a century.

With the assistance of Caroline, the third generation of Astor males and their families moved from their long-standing LaFayette Place townhomes to twin brownstones on Fifth Avenue in 1859. Caroline foresaw a need for the older established families in New York to separate themselves from those who were considered nouveau riche. The new Astor brownstones at 338 and 350 Fifth Avenue became the setting where Caroline would climb the social ladder to be crowned queen of New York Society and where Charlotte entertained a more refined crowd of writers and artists next door.

The Astors and the older New York families considered themselves the ancien regime, or the American Aristocracy, and they began to further barricade themselves from the new industrialists capitalizing on the laissez-faire attitudes of economy and government. Rules of etiquette and ritual were created which mimicked those of the ruling class in England and Continental Europe. To be one of the elite, you not only needed to understand the rules and live by them, but you also needed entry into this prestigious group. The battle lines had been drawn for a war Caroline would lead for several decades.

Shortly after the Civil War, the railroad and transportation industries boomed. Unfortunately, John and his partners experienced the humiliating loss of their key holding of the Hudson River Railway through its forced sale to the magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt. Astor’s line connected New York City to Albany along the eastern shore of the Hudson River: it was the vital and missing piece needed to create Vanderbilt’s monopoly over the New York rails and beyond to Chicago via the Lake Shore & Michigan line. The sale was forced when Vanderbilt stopped allowing the Hudson River Railway trains to connect at the city of Hudson, which in turn halted all rail traffic traveling from New York City to Albany. The situation was an embarrassment to the Astors, and quite possibly one of the reasons the Vanderbilts were kept out of New York’s upper society for over twenty years.

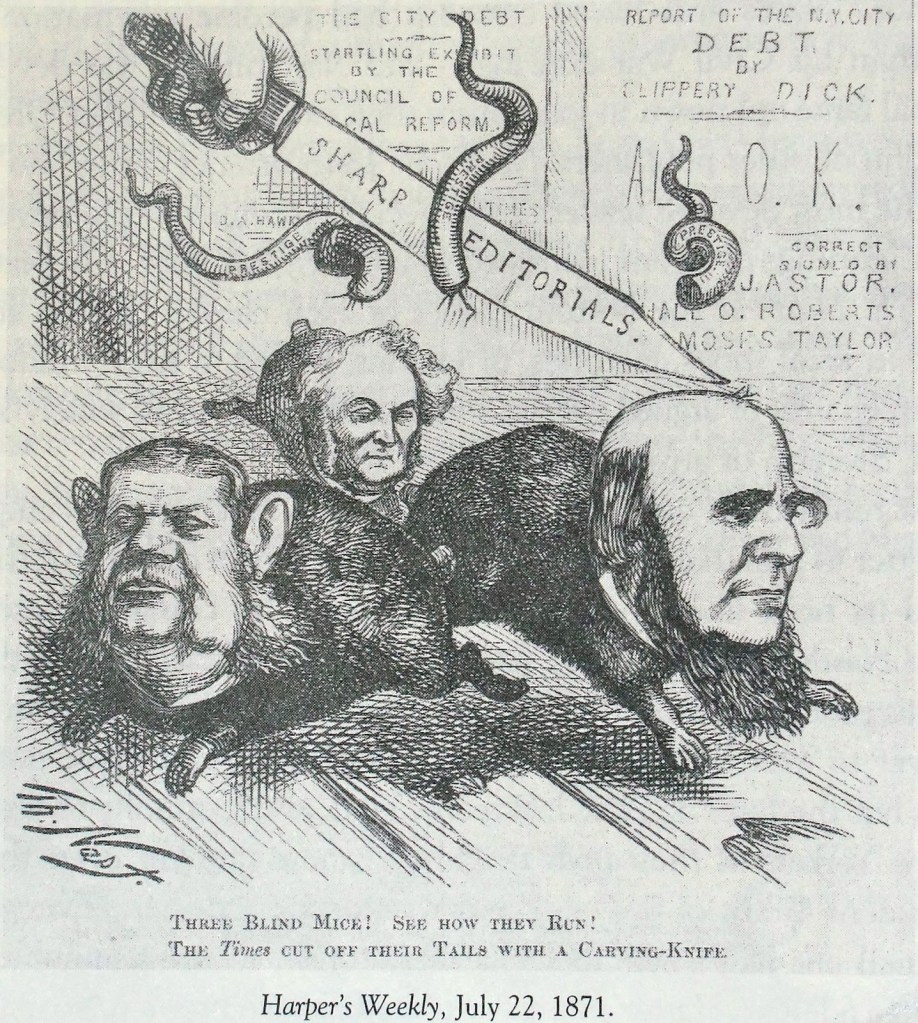

As with his father, John was deeply entrenched in Tammany Hall. His tie to the corrupt political machine was through donations to their campaigns and the enlistment of their help with legislation relating to property and real estate. Corruption was rampant with not only Tammany politics, but also with ruling legislation and even the police force: it was easy to buy what you wanted if you could pay the right price. When concerns of embezzlement and extortion at City Hall surfaced in the late 1860’s, John was named as a member of a committee which, after reviewing the City’s financials for only six hours, attested that all was correct and completed in a faithful manner. It was an attestation that would be blown apart in 1871 when the extent of the pilfering of the City’s Treasury would come to light via an expose in the New York Times. John never took responsibility for anything the committee did or didn’t question during their investigation of the books. The situation, when added to the lengths the Astors went in preventing the northern spread of the population in the City and their longstanding stranglehold of valuable property, further cemented the Astor name to be synonymous with ruthlessness and callousness.

In 1871 John Jacob Astor III started the Knickerbocker Club with several friends to further distance themselves from the vulgar new millionaires now being allowed entry into the once prestigious Union Club. By the following year, William and Caroline’s children were old enough to be left to the care of servants and Caroline had the fortuitous opportunity to meet the social dynamo Ward McAllister in Newport, Rhode Island. Together, she and Ward would establish the list of four hundred people who belonged in New York Society’s elite echelons. The determining factor for this group was a group of twenty-five men named the Patriarchs: gentlemen who could claim at least three generations of wealth and position in New York. Between the Patriarchs and the Knickerbocker Club, great swaths of the the nouveau riche upstarts were excluded, including the Vanderbilts and the Belmonts.

While her control of New York became more fluid and unpredictable as time went on, Caroline maintained a tight leash on society in Newport, Rhode Island during the summer months. It was here that she could fully exercise her extravagance and wealth by hosting only the very best of society. William bought Beechwood for her in the 1880’s, thirty years after John and Charlotte bought their own Newport home, called Beaulieu. As in everything Caroline did related to Charlotte, Beechwood was larger and far more elegant than the other Astor mansion on Bellevue Avenue: it boasted sixty-two rooms at a cost of over $2,000,000 after renovations. Beechwood was the setting of grand parties and dinners which cost $200,000 or more, including an extravagant party where the dining room table covered in a thick layer of sand. Guests were given silver- and gold-plated shovels and buckets as party favors and encouraged to dig for treasures of rubies, sapphires and diamonds.

The race was on for other hostesses to outdo each other and Caroline used the vast Astor wealth at her disposal to maintain her reign as the head of her elected society. Those whose money was earned and not inherited were not worthy of her time or presence. Within the next decade several other families bought up property and built homes around Beechwood which were bigger and grander. The same was also occurring on Fifth Avenue in New York as well and Caroline’s reign was soon to be tested.

In 1883, Alva Vanderbilt broke into the Astor Four Hundred with the clever exclusion of an invite for Caroline and her daughter, Carrie. Alva was hosting a grand costume ball to celebrate her new Fifth Avenue home which she designed with Richard Morris Hunt. Over 1200 invites were sent out to the cream of the crop in New York Society: everybody who was anybody was included on her guest list, except the Astors. By this point, Caroline had begun referring to herself as the Mrs. Astor, to differentiate from her sister-in-law as well as her nephew’s wife. When asked why Caroline and Carrie had not been given an invite, Alva responded “we’ve never been introduced… how could I invite a stranger to my home?” Forced into a corner, Caroline left her monogrammed and gilt-lettered Mrs. Astor calling card with Alva’s butler. She then spent the fifteen minutes necessary in Alva’s drawing room to meet society’s standards of acquaintance in order to gain the invite. The boundaries of New York Society’s elite had shifted to now include the upstart Vanderbilts. However, Caroline made sure to arrive to the Vanderbilt party late and was reported to have worn all of her diamond jewelry with her costume: it was a symbolic gesture akin to donning armor in the battle to retain her hold at the top of New York Society.

When John Jacob Astor III died in 1890, a similar theme to that of his father’s passing fifteen years prior resounded: there was nothing to remember him by. The paltry two million dollars in charity donations made at his wife’s urging were a tiny drop in the bucket of an $80 million estate. Again history repeated itself: the Astor heir had doubled his inheritance, but had left no positive lasting impression behind. His son, William Waldorf Astor packed up, turned 338 Fifth Avenue into the thirteen story Waldorf Hotel (instead of livery stables, as he had originally planned) and left for England and a viscountcy.

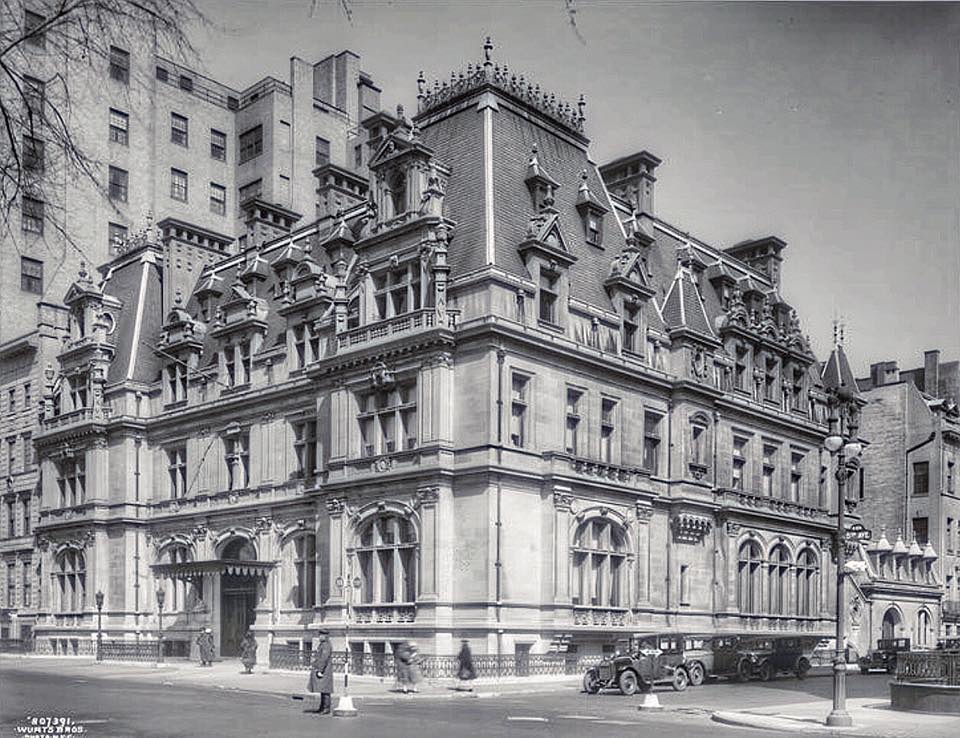

With William Waldorf’s departure across the pond, Caroline’s hand was again forced: there was no way she could remain in her brownstone with a “glorified tavern” residing next door. After holding out for a year amidst the noise and disruption of the hotel’s construction, her home at 350 Fifth Avenue was also torn down. Her son, Jack, had the Astoria Hotel erected in its place to compete with his cousins’s hotel. It was time for Caroline to move farther north: the plan for the renaissance chateau at the corner of 840 Fifth Avenue and 65th Street was born.

William Backhouse Astor Jr died in 1892 of an aneurysm while he was in France. Overshadowed by his father, his older brother and even his wife, he became a mere footnote in history while his wife reigned supreme over a New York Society he disdained. It was the Mrs. Astor and her rise to lead the elite of the Gilded Age that people remember, not his philandering, womanizing, horse breeding or yachting.

Caroline suffered with partial dementia toward the end of her life and because of her notoriety, became a neighborhood spectacle. The constant gawkers outside her home caused her to avoid windows and hide behind the curtains of her new palatial mansion. It took three New York hostesses to fill her shoes when she stepped down from her role and her death in 1908 marked the beginning of the end of the Gilded Age. Three years later, in 1911, Jack hosted a housewarming party with over 200 guests to celebrate the completion of the home at 840 Fifth Avenue. He asked Ruth Livingston Mills of Staatsburgh, one of society’s three leading matrons, to be his hostess in place of his mother (he was in between wives at the time). Just one year later Jack perished on the Titanic at the age of 48. At his death, he was said to have been worth $87 million.

It was the end of a glorious era of massive excess and horrendous poverty. As World War I played out across the globe, America had changed and the cost of maintaining the large palatial mansions was no longer worth it (nor were they affordable with the new taxes levied) to those who had inherited them. The large chateau at 840 Fifth Avenue was demolished after its contents were auctioned off in 1924 by Vincent Astor, Jack’s son. Both the Waldorf and the Astoria hotels had been merged into the Waldorf-Astoria by a walkway connecting them, but the buildings would only stand for thirty or so years after they had been built; they were torn down in 1929 to make way for the Empire State Building. What a site it must have been to walk down Fifth Avenue over one hundred years ago when it was the Millionaire’s Mile…

Sources: The Astors, Derek Wilson, 1993 and Dynasty: The Astors and Their Times, David Sinclair, 1984